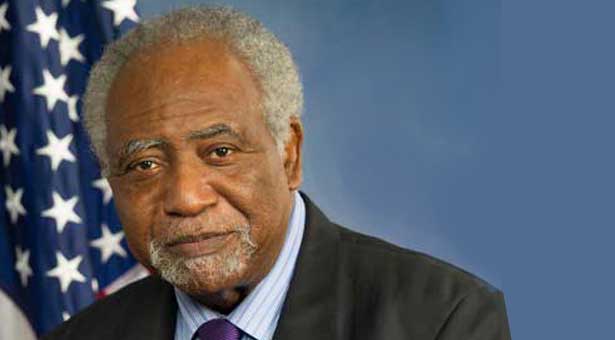

By Rep. Danny K. Davis (D-Ill.)

Austin, Ill., the community where I live, in the heart of the Congressional District I represent, includes the zip code with the largest number of releases from the Illinois Department of Corrections; 90 percent of the individuals released are African-American males.

When these (mostly) young men are released from prison, they find all of the social and economic barriers they faced before incarceration, plus additional barriers to jobs, housing, education, and almost every aspect of daily life. One in every 40 adults is unable to vote because of a current or prior felony conviction. For African-Americans, the rate is one in 13.

Over the past 50 years, our penal system has become an increasingly urgent issue that has reached crisis proportions, especially in the African-American community. There were about 338,000 individuals in prison in 1970. Today, that number is over 2,000,000. That number has grown every decade over the last half century without regard for the falling crime rate. The Federal Bureau of Prisons appropriations increased more than $7.1 billion from FY1980 ($330 million) to FY2016 ($7.479 billion)

Every year in the United States, 641,000 people walk out of prison gates, and, every year, people will go to jail over 11 million times. This is called jail churn. It happens, because most of the people who are jailed have not been convicted. Some will make bail within a short time; some are too poor and will stay in jail until their trial. Some will be convicted of misdemeanors and will receive sentences of under a year.

African-Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of Whites and while they make up 13 percent of the U.S. population, they are 40 percent of the prison population. In some states that rate was 10 times or more. Research from numerous scholars and organizations has been instrumental in developing a growing bipartisan consensus on the forces driving this great disparity and the additional costs this disparity places on the African-American community and society in general.

A recent report by The Sentencing Project notes:

“Proposed explanations for disparities range from variations in offending based on race to biased decision-making in the criminal justice system, and also include a range of individual level factors such as poverty, education outcomes, unemployment history, and criminal history.”

During my years in the Congress, I have fought to reduce disparities in our criminal justice system. I believe my “Second Chance Act” and other initiatives, coupled with the fiscal realities that these disparities have imposed on the states and federal government, have helped to create a space for bipartisan debate and consensus about how best to reduce these disparities.

I believe that debate and consensus laid the groundwork for some gains we saw during the Obama presidency.

The Sentencing Project notes:

While states and the federal government have modestly reduced their prison populations in recent years, incarceration trends continue to vary significantly across jurisdictions. Overall, the number of people held in state and federal prisons has declined by 4.9% since reaching its peak in 2009. Sixteen states have achieved double-digit rates of decline and the federal system has downsized at almost twice the national rate. Twelve states have continued to expand their prison populations even though most have shared in the nationwide crime drop. States with the most substantial prison population reductions have often outpaced the nationwide crime drop.

Recommended For You.

Be the first to comment