By Hamil R. Harris and David Martosko

For more than seven months, the U.S. Capitol Police officer who shot and killed Ashli Babbitt, an unarmed protester climbing through a broken window in a hallway of the U.S. Capitol on January 6, has remained anonymous.

Though his name was known to U.S. Capitol Police, congressional staffers and federal investigations, no one would divulge it. The secrecy fueled months of online speculation.

Babbitt’s family alleged a coverup.

“The U.S. Congress wants to protect this man. He’s got friends in high places and they want to protect him,” said Maryland attorney Terry Roberts, who represents the family. “And they’ve done a pretty good job of it. … I don’t think it’s a proud moment for the U.S. Capitol Police or the U.S. Congress.”

Roberts told Zenger Wednesday night that the shooter was “Lieutenant Michael Leroy Byrd.”

Byrd’s attorney, Mark Schamel, did not dispute the positive identification. It adds to information from other sources who told Zenger in recent months that Byrd was the January 6 shooter. None of them would say so on the record.

Byrd is a controversial figure with a record of mishandling firearms, including once leaving a loaded pistol in a Congressional Visitor Center bathroom. Roberts said Byrd’s decision to fire his weapon on January 6 indicated his unfitness for duty.

“If I was a congressman, I’d be very concerned about him carrying a gun around me,” he said.

Typically, police officers who shoot civilians are named publicly. But the January 6 riot and the riots that erupted after George Floyd was killed by a Minneapolis police officer, divided the country along political, class, and racial lines—making officials cautious about revealing the name of a Black police officer who killed a white protester.

Roberts said race was “clearly a factor” in the decision to shield Byrd from public scrutiny.

“It’s something that has to be considered, because it’s just a clear pattern in the United States,” he said. “A white cop kills a Black individual? Their name is out there within a day. It’s all public. And look, a police officer is a public official. There should not be any exception for this.”

U.S. Capitol Police officials, police union representatives and government officials had repeatedly claimed that disclosing the officer’s identity would put his life and his wife’s in danger—and subject them to racial slurs. Lt. Byrd’s family roots are in Jamaica, according to one of his neighbors.

After not naming Byrd publicly for months, Babbitt’s lawyer said he became skeptical when he learned Wednesday that the officer was set to appear with Lester Holt in an NBC News broadcast the following day—and that NBC had already taped the interview.

“They put out there that his [Byrd’s] life would be in danger if he came forward, and we know now that that can’t be true because he’s coming forward on his own,” Roberts said. “So, you know, he used that as an excuse.”

Roberts, the Babbitt family’s lawyer, is planning a wrongful death lawsuit naming both Byrd and the U.S. Capitol Police as defendants. The suit has yet to be filed due to a federal law requiring a months-long notice period before such actions can be brought against government agencies.

The family is crowdfunding their lawsuit. The effort has raised more than $76,000 of their $500,000 goal.

Byrd was not justified in killing Babbitt, Roberts said, because he had no reason to believe the unarmed Babbitt posed a threat to himself or others. Byrd fired the only shot at the Capitol on January 6, and Babbitt was the only person there killed by gunfire that day.

Byrd’s own lawyer, Mark Schamel, insisted on his client’s anonymity since April, loudly, and always citing the officer’s physical security. He parried Zenger’s questions about his unnamed client for nearly four months.

“Running the name of a hero who has the need for 24-hour protection is disgusting and indefensible,” Schamel said July 9 in a text message. He was responding directly to a question that mentioned Byrd by name.

“Is Byrd’s decision to grant a public interview an indication that fears for his safety were unfounded?” Zenger asked him during a phone call Wednesday night.

“Not in any way, shape or form,” Schamel replied, before declining any further comment. Minutes later he texted: “I can confirm that my client is a hero. My client justifiably used force to protect members of Congress from an imminent threat posed by violent rioters and that he shot the first rioter who breached the inner sanctum of the House of Representatives and … there is no basis in law or fact for a civil case against him or the Capitol Police.”

“If the violent insurrectionist who died [Babbitt] had survived,” Schamel wrote, “she would have been indicted on felony charges and would have been on her way to prison with her fellow insurrectionists.”

Most of the hundreds of January 6 protesters who have been formally indicted are charged with trespassing, vandalism or similar minor offenses. Convictions for these offenses seldom draw jail terms.

Byrd shot Babbitt, a decorated U.S. Air Force veteran who served in the Gulf War, while she attempted to climb through a smashed windowpane and illegally enter the Speaker’s Lobby, an area adjacent to the House floor. Amateur video shows Byrd’s arm stretching out and holding still before he fired a single shot across the doorway at the 35-year-old woman.

It appears from footage that Babbitt, wearing a backpack, may not have seen Byrd before a round from his semiautomatic weapon struck her. The coming civil suit may hinge on whether or not Byrd warned Babbitt before he fired. Publicly available videos don’t include any audio of Byrd issuing a warning or announcing that he has his gun drawn.

Little is known publicly about Byrd, age 53. The U.S. Department of Justice and Capitol Police have remained tight-lipped about him, even as both agencies issued press releases, short on details, announcing his exoneration. Many who live near the longtime Capitol Hill police officer in Brandywine, Md. have hunkered down, not answering their doorbells when Zenger reporters visited to ask about their personable neighbor who became a sudden recluse after the shooting.

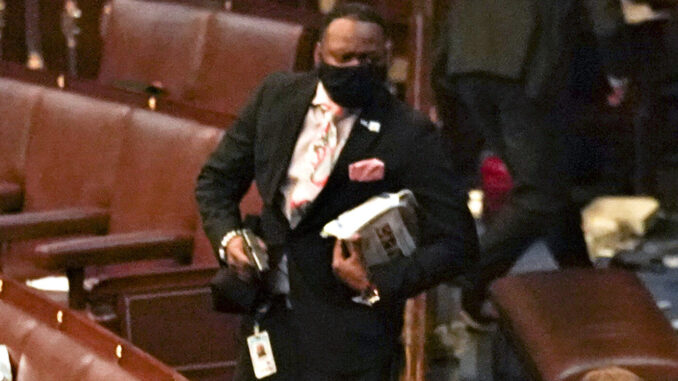

A January 6 news photograph of the House floor, where Byrd was in command of security, shows him with a pistol in his right hand. In the photo, Byrd is rushing to help other officers and special agents as they defend a barricaded doorway from angry protesters—the same doorway many presidents have walked through to address Joint Sessions of Congress.

The photo, captured by Bloomberg News and distributed by Getty Images, shows a distinctive bracelet — a pattern of white beads interrupted by solitary black beads — worn on the wrist of his shooting hand. That same bracelet is visible in amateur video, on Byrd’s right hand, the moment he opened fire.

Byrd’s identity has surfaced occasionally, in most cases on Twitter where partisans have vented about his ability to sidestep public attention after killing a civilian in the line of duty. A July report from Real Clear Investigations briefly noted an unguarded moment during a Feb. 25 House hearing when Timothy Blodgett, the acting House sergeant at arms, let Byrd’s name slip.

Explaining why his staff didn’t participate in radio traffic with U.S. Capitol Police during crisis incidents, Blodgett told lawmakers: “We communicate with our staff via cellphone, text message. We were in close contact. The situation you discussed where Officer Byrd was at the door, when Ms. Babbitt was shot, it was our sergeant-at-arms employee who rendered the aid to her at that site.”

C-SPAN’s transcript of that House Appropriations subcommittee hearing omits Byrd’s name. A transcript available from CQ Transcripts, a unit of the news organization CQ-Roll Call—formerly known as Congressional Quarterly—includes it.

The post Exclusive: Police Lieutenant Who Killed January 6 Capitol Rioter Ashli Babbitt Finally Identified appeared first on Zenger News.

Recommended For You.

Be the first to comment