“If we must die, let it not be like hogs, hunted and penned in this inglorious spot while round us bark mad and angry dogs making their mockery of our accursed lot. Like men we will face the murderous and cowardly pack pressed to the wall, dying but fighting back.” – Clyde McKay

By Cheryl Mainor

Contributor

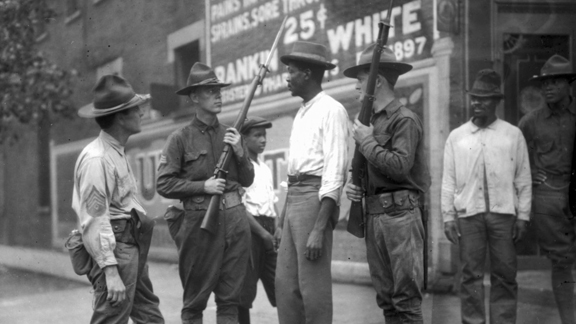

The poet and author Clyde McKay wrote the poem, “If We Must Die” after a series of violent attacks against Black people Americans in the summer of 1919. Author, James Weldon Johnson coined the term “Red Summer” to describe those events. A century ago, hundreds of Black people were killed during those events, and yet, the nation has built few memorials to those dead. The Red Summer deserves to be remembered.

1919 was a sort of a turning point for the United States. The first World War had ended in November 1918, and troops were returning to an America that was rapidly changing. Women would soon gain the right to vote, and Prohibition would begin an experiment in banning alcohol.

The army was segregated, but some Black troops were put under French command because White American officers were not comfortable commanding Black troops. Many White Americans blamed the French for treating Black soldiers as equals and planting ideas in their heads. Called soldiers of democracy, Black veterans came back to America ready to demand civil rights. W.E. B. DuBois wrote “We return, we return from fighting, we return fighting.”

The army was segregated, but some Black troops were put under French command because White American officers were not comfortable commanding Black troops. Many White Americans blamed the French for treating Black soldiers as equals and planting ideas in their heads. Called soldiers of democracy, Black veterans came back to America ready to demand civil rights. W.E. B. DuBois wrote “We return, we return from fighting, we return fighting.”

For Black Americans, 1919 marked three-hundred years since the first African slaves were brought to the American colonies and they had begun to start culling for change. 1919 was a time of anxiety for the United States and the world. The first World War had ended, but other social movements and economic conditions contributed to an anxious time. Inflation was rising, labor strikes were common. In Russia, the Bolsheviks had overthrown the Czar; Americans feared Bolshevik agitation might come to their shores. Anarchist bombings were common, and the economy was in flux. And, in northern cities, Whites were afraid of the new Black migrants and economic competition.

The Great Migration would eventually send millions to the North and industrial Midwest fleeing violence, segregation, and lack of economic opportunity in the South. Unfortunately, they were oftentimes greeted with the same in places where they relocated. While they were at first unconcerned, Southern employers eventually worried about the loss of cheap labor and how to stem the tide of the exodus.

From spring into fall of 1919 these tensions exploded into the series of violent episodes in which hundreds of Black Americans were killed and served as a wake-up call. But it also spurred a movement in which Blacks in America, fought back; sometimes, for the first time.

An early episode of violence occurred in Jenkins County, Georgia in April. A Black church service was interrupted when two White officers arrested a Black man named Edwin Scott for possession of a pistol. A wealthy Black farmer named Joe Ruffin offered to pay his fine, but the officers demanded cash instead of a customary check. When Ruffin tried to pull him to the car, an officer struck him with his pistol, which discharged and knocked Ruffin unconscious. Ruffin’s son, an Army veteran thinking his father was dead, shot and killed one of the officers. In the ensuing gunfight, the second officer was shot and then beaten to death. As the word spread, hundreds of White men rushed to the town, bent on revenge.

Ruffin surrendered to the local sheriff, who protected him from a mob intended on lynching him. But the mob then caught and lynched two of his sons as well as another Black man who was in the area. They also burned the church and three other Black churches as well as three Masonic lodges in the area. Ruffin was taken to another county by the sheriff and put in jail there. Repeated attempts to try him for murder and manslaughter were unsuccessful but he was left impoverished due to his legal fees. He left the county moving to South Carolina as it was not safe for him to remain in Georgia. No charges were ever filed against the men who killed his two sons and the other man, or who destroyed property.

On July 19th, in Washington, D.C., a White woman claimed she was jostled on the street by two Black men. One of the men was questioned by police and released, but a rumor began among some White Army veterans that the man had committed rape. White mobs started a four-day riot, attacking and beating hundreds of individuals and damaging businesses. When the city’s police refused to intervene, Black residents fought back, and defended their neighborhoods with firearms. There was shooting and attacks from both sides until then President Woodrow Wilson reluctantly sent in two hundred Army troops to intervene. When it finally ended on July 25th, at least forty people had died from gunshots and street fights with over 150 people wounded.

In Chicago, a weeklong riot was set off on July 27th, when a Black teenager named Eugene Williams and three others were on a raft in Lake Michigan to escape the sweltering heat. Being taken along with the current, they floated into the area of a segregated White’s only beach, where a White man thew rocks at them hitting Eugene in the head and knocking him into the water where he drowned. When Black witnesses complained to the police and tried to have the man arrested, the police did nothing. A fight broke out between the Black people and a White mob, and the riot ensued, lasting for five days.

The vast majority of the acts of murder, arson and property damage were perpetrated by White gangs against Black neighborhoods of Chicago’s South Side. Police did little to protect Black people and the State’s Attorney accused the police of arresting the Black rioters while refusing to arrest White rioters. Illinois was forced to call in the militia to restore order. In the end, 23 Black and 15 Whites were killed during the rioting with more than five hundred injured and over one thousand Black residents were left homeless due to arson.

Other riots broke out in twenty-two other cities including Omaha, Nebraska with 120 Whites being arrested but none found guilty. The deadliest event took place in Elaine, Arkansas on September 30th. When a group of union Black sharecroppers was planning a meeting with White farmers to discuss how to obtain farer wages for their labor, members of the farmers group insinuated that Communists were behind the sharecroppers’ efforts, stoking the fear and tensions of the nation that the Russian Revolution was coming to America.

When two White deputies showed up at the meeting, they clashed with armed Union guards, resulting in the death of one of the deputies. The local sheriff called for a posse to aid in the arrest of those responsible for the killing. When rumors spread of a possible insurrection by the Black people, a mob of over one thousand White men showed up indiscriminately killing Black men, women, and children. Estimates of those killed are between 100 to 500 killed by the mob. The Governor called in troops to stop the violence and arrested 285 Black men. Poll taxes and other impediments made it impossible for a Black defendant to receive a trial of their peers. Sometimes armed White mobs were outside and inside the courtroom. No White men were arrested or charged for their brutal violence.

These represent just a few of the more than twenty-five violent riot events throughout America during the Red Summer and lasting into the late fall of 1919. Reports indicate that between 1889 to 1919 more than 3000 Black people had been lynched. States rarely prosecuted anyone for lynching a Black person. While these incidences fighting back represented incredible courage and acts of self-determination, it would be another 5 decades before acts of terror and lynching perpetrated on Black Americans would cease, for the most part.

Many of the Black men who fought back in D.C and Chicago were military veterans who were ready to defend themselves, their families, and their communities with their training. The Red Summer riots marked a difference from previous years when Black people were attacked and did not or could not defend themselves. The violence made one Veteran, Henry Haywood said, “I’d been fighting the wrong war; the Germans were not my enemy, the enemy was right here at home.”

Recommended For You.

Be the first to comment